Can Multigenerational Housing Save America?

It’s tough out there.

The last 24 months brought a torrent of ominous headlines about mental health. Seniors are lonely. Parents are stressed. Teens are anxious. These are largely American epidemics and have contributed to the United States ranking lower than ever in this year’s World Happiness Report.

Some blame technology and social media. Others blame economic conditions like surging costs, stagnant wages, and a national housing shortage, which have put the American Dream out of reach for many.

As a Gen X dad, I’ve felt the impact of all these trends on my own life. Last summer, my mother took a fall. After exploring a range of options, my sister and I decided to move her into an assisted living facility. It’s perfectly comfortable, but also deeply isolating, a place where each person’s individual loneliness seems to compound in the aggregate.

Early in our marriage, my wife and I talked about having the kind of home that could accommodate our parents one day. But we could never find the right kind of space in New York City, and our lives weren’t set up to decamp to the suburbs or beyond. The idea remained a “maybe someday” that has now, sadly, passed.

Like so many others, we feel the isolation of modern parenting, relying on books, podcasts, and social media for wisdom, and a color-coded Google calendar full of activities and babysitter hours for childcare, rather than the advice and support of our elders. The stress of figuring it all out on our own, while also managing workplace and financial stress in today’s hyper-productivity culture, has many parents at their wit’s end—48% to be exact. This stress absolutely trickles down to our children, making the ground they walk on that much less firm.

Noticing how the headlines mirrored my own experiences, I spent much of the past year studying these dovetailing crises and trying to figure out where we went wrong. The answer, I found, lies about 100 years in the past.

From villages to white picket fences.

For millennia, humans lived in tightly-knit villages of around 150 people, Dunbar’s number for the amount of stable social relationships a person can maintain. In these communities, each generation played a distinct and vital role. Elders served as repositories of knowledge, sharing history, traditions, and practical skills with younger villagers. Young and middle-aged adults were the primary laborers, providing food, shelter, and security. Children learned through observation and participation, absorbing the culture and developing skills necessary for their future roles. This interdependence fostered a strong sense of community, with each age group contributing to the collective well-being and continuity of the village.

In the late 18th century, due to population growth and the twin forces of industrialization and capitalism, cities and suburbs began to replace villages throughout the world. In most countries, especially across Asia, Africa and Latin America, multigenerational living has remained the norm despite densification. The United States is a glaring exception.

Prior to the 1930s, the typical American household would have included elders living with their children and grandchildren. But beginning in that decade, federal housing policy shifted to promote suburban, single-family living as a wealth generator for white nuclear families.

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), created as part of President Roosevelt’s sweeping New Deal, made homeownership affordable for young, middle-class families— white ones—through long-term, low-interest mortgages. Their underwriting manuals explicitly favored suburban, single-family homes, with architectural layouts that divided the home into age-specific zones: children’s bedrooms, master suites for parents, and no room for extended family. Federal zoning laws enacted alongside the New Deal reinforced this design by restricting the construction of multifamily units, in-law apartments, and mixed-use neighborhoods. Local governments, likewise, implemented single-family zoning that structurally excluded multigenerational living arrangements.

As these policies took root, age-restricted communities, such as Youngtown (1954) and Sun City (1960) in Arizona, began popping up, catering specifically to retirees. Enabled by New Deal and Great Society programs like Social Security and Medicare, older Americans could now afford to live independently from their children and grandchildren. While this independence was often seen as empowering, it also created generational separation.

Cultural ideals of the time—promoted by developers, advertisers, and policymakers—framed the nuclear family in a detached suburban home as the pinnacle of modern American life. Taken together, these policy and cultural shifts not only redefined what an "ideal" household looked like, but also made multigenerational living seem outdated or even undesirable in mainstream America.

The downside of progress

Without realizing it, mid-20th century Americans became the first participants in a radical experiment of segregating society by age. Marc Freedman, founder of generational togetherness nonprofit CoGenerate, writes, “It was hardly a nefarious plot. Soon young people were spending their time in schools, middle people in workplaces, and older people in a range of (enormously creative) social inventions including senior centers and retirement communities. However, for all the uplifting features of this peer-focused reorganization of life, the end result can be characterized as a grievous wound.”

While age segregation brought unprecedented educational attainment, GDP growth, and longevity gains, as well as access to homeownership, it also eroded a social and cultural fabric that provided built-in socialization and mutual support.

We are seeing the consequences now. The loneliness epidemic is a staggering example. In a 2020 survey by Cigna, more than half of US adults (58%) are considered lonely. Young adults (18–25) are among the loneliest: 61% reported feeling lonely “frequently” to “all the time” in a recent Harvard study. These feelings can have serious consequences; they’re a driving force behind the rising rates of self-harm and suicide among American adolescents. For older adults, social isolation can likewise be life-threatening, increasing the risk of a heart attack and/or death from heart disease by 29% and stroke by 32%. Meanwhile, the U.S. Surgeon General is sounding the alarm on loneliness and stress for another group—parents. Maybe this has something to do with our abysmal happiness ranking?

For everything we’ve sacrificed in terms of physical and mental health, age segregation has failed to deliver lasting financial security for most Americans. Over the last 70 years, with the decline of labor unions and the erosion of workers' bargaining power, capital gains have been concentrated among the top 1% of earners. Since 1972, the cost of living has risen sharply while real wages have remained completely stagnant. Home prices, in particular, have soared by 132%. These dynamics, combined with a national housing shortage, explain why nearly two-thirds of Millennials are unable to afford a home.

Where do we go from here?

If it takes a village, we’d better start building some.

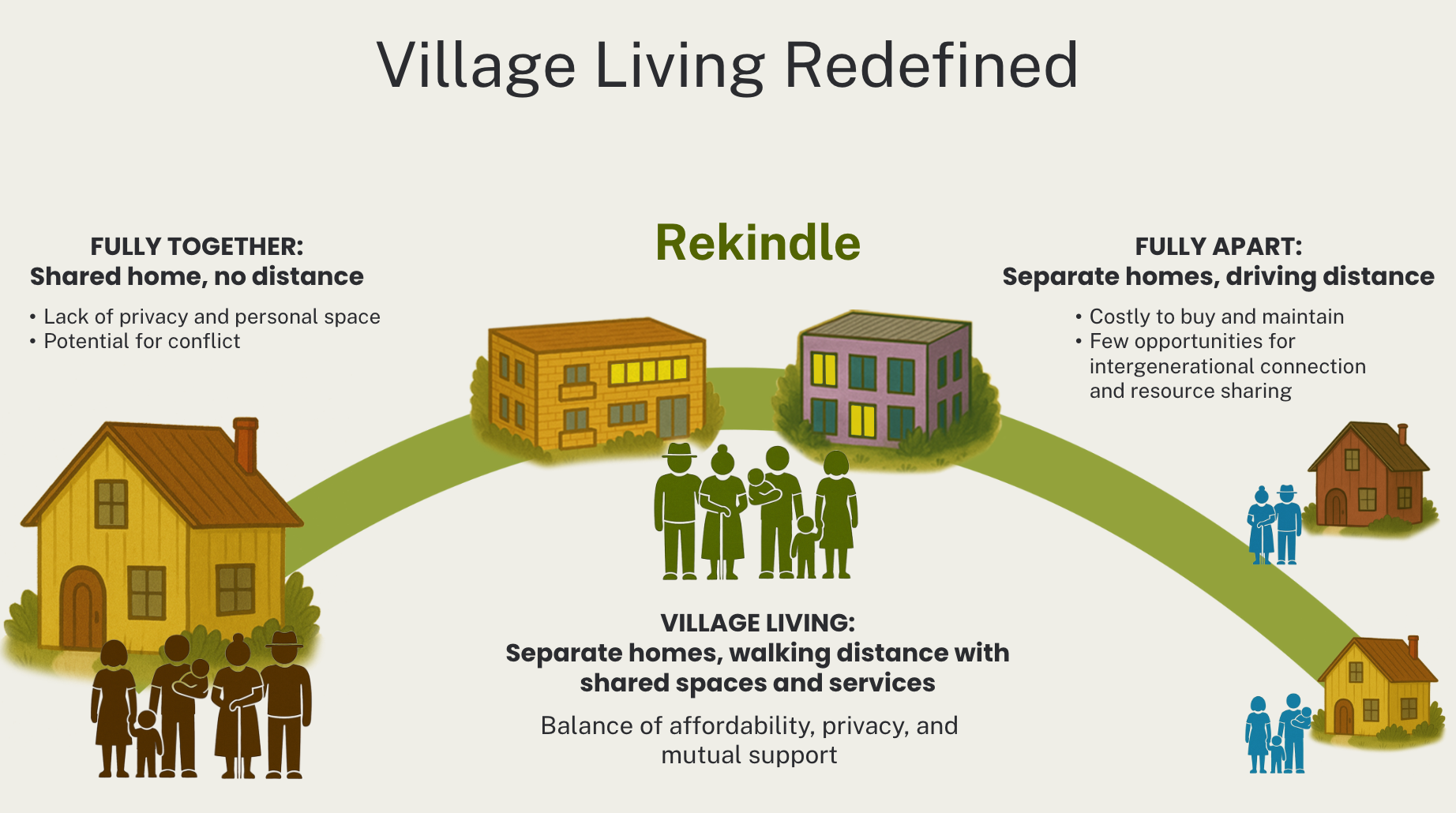

In direct answer to socio-economic breakdown, multigenerational housing is on the rise. Sixty million Americans are now living in three- or four-generation households, a four-fold increase since the 1970s. But very few American homes today were designed with multigenerational living in mind. Many families in these arrangements end up feeling cramped and on top of each other. One man I interviewed said he is proud to be a “diaper-changing grandpa” and a daily presence in his grandson’s life, but added, “I don’t want to see him at breakfast every day.”

I heard versions of this sentiment again and again over the course of my research—the grandparents and adult children want to be close, but not too close. Specifically, “five minutes away" was most commonly cited as the ideal distance. We know that 25% of Baby Boomers plan to retire near their children and grandchildren, but as of today, there are no dedicated communities for multigenerational families to live in close proximity but under separate roofs. Multigenerational housing concepts from America’s biggest homebuilders, like Lennar and Tri Point Homes, continue to serve up a one-roof model.

Rekindle is a new venture to mainstream multigenerational housing in America. We’re in the process of designing a village-scale community that will offer multi-roof solutions for multigenerational families within an intentionally planned, walkable campus. Shared amenities like co-working, lifelong learning, dining, health and wellness services, a garden and other recreation areas will bring the generations together for meaningful community building. Overall, the community will strike a balance between affordability, privacy and mutual support that cannot be achieved by living fully together or fully apart.

Our first project is taking shape on the US East Coast. While future communities will be designed to suit local context and prospective residents, all of our communities are intended to:

- Combat loneliness, stress, and anxiety

- Make childcare and eldercare more organic and affordable

- Allow seniors to age gracefully in place

- Create shared economies where multiple families can pool resources

- Give people across all generations a sense of purpose and belonging

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay in the loop, or shoot us a note to get involved.

“We need to realize that it’s not a matter of us going back. It’s a matter of us going forward to something that is better and healthier for many families. We said we don’t need each other — when in fact we do need each other.” Donna Butts, Executive Director, Generations United.